By Ray Rogers, from the website https://www.shroudstory.com/

I must admit, with some embarrassment, that until a few years ago I knew nothing about the Shroud of Turin. And when I first did read about it, while on a flight to Miami, I laughed out loud, something I rarely do alone in the company of strangers.

How ridiculous, I remember thinking. How can anyone think the Shroud of Turin is real: the actual burial shroud of Jesus? The fact that the Shroud of Turin has an image on it, believed to be a picture of Christ, made it seem beyond preposterous.

I was reading Desire of the Everlasting Hills, Thomas Cahill’s book about the apostolic era. Having enjoyed Cahill’s previous best seller, The Gifts of the Jews, I thought I would enjoy his newest book. And I was enjoying it. Suddenly, with no logical reason that I could see, Cahill introduced the Shroud of Turin. It might have been a treasure of the early church, he thought. That is when I laughed — out loud.

I remember being surprised that I knew so little about the Shroud of Turin. Then in my mid-fifties, I had always been an avid reader of history, particularly early church history. I could not recall ever reading anything about the Shroud of Turin. It was so far from being something I cared about that I never paid it any attention. Thus, when in 1979, Walter McCrone, a world renowned forensic microscopist, claimed that he found paint on a few Shroud fibers, I didn’t notice the story. McCrone, having noted that the shroud had suddenly appeared in 1356 in the hands of a French knight who would not say where it came from and that a local bishop soon thereafter claimed that an artist “cunningly painted” it, declared it a painted fake. Had I noticed the story in 1979, I would have certainly accepted his conclusion. It would have made sense to me.

A decade later, when three radiocarbon dating laboratories, using carbon 14 dating, supposedly proved the Shroud of Turin was medieval, I didn’t notice. Had I, I would have certainly accepted the conclusion. I trust science. I did then, and more than ever, I do now.

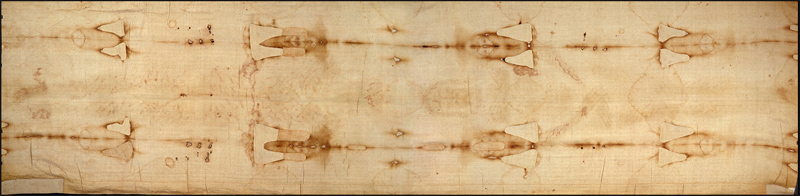

Moreover, I am naturally skeptical about any relic with a historical footprint in medieval Europe. The year 1356 was a time of unbridled superstition in demons, witches, magic, and miracle-working relics. It was a time of frequent famine and the Black Death plague. It was a time of extreme economic and political turbulence and of war. The same year that the Shroud was first displayed publicly in the small French village of Lirey, nearby, at the battle of Poitiers, England’s Black Prince defeated the French and captured King John II. Adding to the political turmoil, the Pope was in Avignon, not Rome. Indicative of the thinking in this age, some believed that the plague was God’s retribution on the whole world because the Pope was not in the eternal city. In this climate of superstition, naiveté and disorder a lucrative market in false relics flourished. And though the Fourth Lateran Council, in 1215, acknowledged the problem, church authorities did little to curb the market in them. Our knowledge of this time in history rightly conditions us to be suspicious of any relic that might appear in Europe at this time. But I had not noticed its history, either. In metaphoric parlance, the Shroud of Turin was never a blip on my radar screen. And it would have likely remained that way were it not for a single enigmatic fact that Cahill mentioned: the picture on the Shroud of Turin was a negative.

I knew something about the subject of negatives. But rather than marveling at this fact, I doubted it. I was so convinced that the Shroud of Turin was a fake that I doubted the images were negatives. I had to see for myself.

I was certain that no artist, no craftsman, no faker of relics, could possibly paint a negative of a human face. To do so is like trying to write your signature upside down and backwards. Our minds are programmed for the way we see things in the world; a world where black is black and white is white. It is relatively easy, with talent and training, to paint a picture of what we see in the world. And an artist, if he is imaginative, like Picasso, can alter that perception in stylistic ways. But the one thing he cannot easily do is to perfectly reverse black and white and all the darker and lighter shades of grey while painting a face.

But imagine, for just a moment, that he could. How would he know he had done it correctly without technology to test his results? A more profound questions is why? In an age so undemanding as the medieval, when any sliver of wood could pass as a piece of the “true cross” and any bramble as a piece of the “crown of thorns,” why bother?

Photographic film, invented less than 200 years ago, creates good negative images. And because that is so, it was finally discovered that the shroud image was a negative when it was first photographed in 1898. Along with new scientific-quality photographs, taken in 1978 and again in 2002, extraordinary details were noticed: contusions and anatomical detail only a modern pathologist could understand. Our minds don’t easily see details in negatives. It is beyond preposterous to think that the Shroud of Turin was painted.

Because the picture was a negative, some have speculated that the Shroud of Turin might be a medieval proto-photograph; an invention, if you believe it, that was used only once for a single fourteen-foot long fraud, and never mentioned or used again until it was reinvented in an age of science. Such speculation is moot. Scientific data conclusively proves that it is not a photograph.

So entrenched was my skepticism, it would take me a year to change my mind about the Shroud of Turin. I learned that McCrone’s identification of paint was a subjective judgment. More sensitive tests, some undertaken at the National Science Foundation Mass Spectrometry Center of Excellence at the University of Nebraska, proved, beyond a shadow of a doubt, McCrone was wrong.

Starting in 2003, new evidence began to appear in secular, peer-reviewed, scientific journals that supported the Shroud of Turin’s authenticity. From these journals we learn that the outermost fibers of the cloth are coated with a layer of starch fractions and various saccharides. In places, the coating has turned into a caramel-like substance, thus forming the images. This suggests a chemical reaction took place. We learn, also, of a faint second image of the face on the backside of the cloth. The second face supports the idea of a chemical reaction and adds more proof that the image is not a work of art or a photograph. And in 2005, we learned that the carbon 14 dating was flawed. In fact we learned that the cloth could very well be 2000 years old.

History and the Shroud of Turin

As science moved forward, new historical information was coming to light. Indeed, there is evidence that the cloth, now called the Shroud of Turin, really was a treasure of the early church; not the Pauline communities with which we are so familiar, but the Church in the East. Edessa, in the Fertile Crescent of the upper Mesopotamia, between the Tigris and the Euphrates, was a major city on the Silk Road and undoubtedly one of the earliest Christian communities. If you traveled from Jerusalem to Antioch, you were two thirds of the way to Edessa. Turn left to go to Tarsus, turn right for Edessa. There is some evidence and a strong tradition that Thomas and Thaddeus Jude (Thaddeus of the 70, Thaddeus of Edessa) went to Edessa as early as 33 CE. There is a legend that they carried with them a cloth bearing an image of Jesus. In 544 CE, a cloth, with an image believed to be Jesus, was found above one of Edessa’s gates in the walls of the city, a cloth that Gregory Referendarius of Constantinople would later describe with a full length image and bloodstains. There is strong evidence that the Edessa cloth is in fact the Shroud of Turin. Numerous writings, drawings, icons, pollen spores and limestone dust attest to this.

How curious these poetic words from the apocryphal Thomasine literature of Edessa seem. They are from the “Hymn of the Pearl,” a poem arguably as old as the first half of the first century. As a figure of speech, Jesus, in the poem, is musing in the first person:

But all in the moment I faced it / This robe seemed to me like a mirror,

And in it I saw my whole self / Moreover I faced myself facing into it.

For we were two together divided / Yet in one we stood in one likeness.

These words resonate with the two head-to-head images we see seemingly reflected on the Shroud of Turin: like a mirror . . . my whole self . . . faced myself facing into it . . . we were two together divided . . . stood in one likeness.

Carbon 14 and the Shroud of Turin

The big issue was always the carbon 14 dating that seemed to show that the Shroud of Turin was medieval. Researchers, who were not experts in radiocarbon dating, but nonetheless convinced the Shroud of Turin was authentic, tried to explain why the scientific dating was incorrect. These explanations – one was that a fire in 1532 changed the age of the Shroud, another was that a bioplastic-polymer growing on the Shroud contaminated the sample – lacked scientific credibility. Scientists, who were experts in radiocarbon dating, rejected these explanations.

In January, 2005, things changed. An article appeared in a peer-reviewed scientific journal Thermochimica Acta, which proved that the carbon 14 dating of the Shroud of Turin was flawed because the sample used was invalid. Moreover, this article, by Raymond N. Rogers, a well-published chemist and a Fellow of the Los Alamos National Laboratory, explained why the Shroud of Turin was much older. The Shroud of Turin was at least twice as old as the radiocarbon date, and possibly 2000 years old.

Peer-reviewed scientific journals are important. It is the way scientists normally report scientific findings and theories. Articles submitted to such journals are carefully reviewed for adherence to scientific methods and the absence of speculation and polemics. Reviews are often anonymous. Facts are checked and formulas are examined. The review procedure sometimes takes months to complete, as it did for Rogers.

It was Nature, another prestigious peer-reviewed journal, that in 1989, reported that carbon 14 dating ‘proved’ the shroud was a hoax. Rogers found no fault with the article in Nature. Nor did he find fault with the quality of the carbon 14 dating. He defended it. What Rogers found was that the carbon 14 sample was taken from a mended area of the Shroud that contained significant amounts of newer material. This was not the fault of the radiocarbon laboratories. But it did show that the carbon dating was invalid.

Immediately after the publication of Rogers’ paper, Nature published a commentary by scientist-journalist Philip Ball. “Attempts to date the Turin Shroud are a great game,” he wrote, “but don’t imagine that they will convince anyone . . . The scientific study of the Turin Shroud is like a microcosm of the scientific search for God: it does more to inflame any debate than settle it.” Later in his commentary Ball added, “And yet, the shroud is a remarkable artifact, one of the few religious relics to have a justifiably mythical status. It is simply not known how the ghostly image of a serene, bearded man was made.”

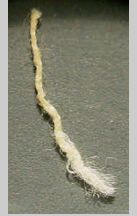

Yellow dye can be seen from spliced thread. Newer material was dyed with alizarin from madder root to match age-yellowed older thread.

Ball, who understood the chemistry of the Shroud of Turin images, rejected a notion popularized by conspiracy theorists that Leonardo da Vinci created the Shroud’s image using primitive photography. He called the idea flaky. He also debunked the sometimes reported speculation that the image was “burned into the cloth by some kind of release of nuclear energy” from Jesus’ body. This he said was wild.

Almost all serious Shroud of Turin researchers agree with Ball on these points. When flaky and wild ideas appear in newspaper articles or on television, as they often do, scientists cringe. Rogers referred to those who held such views as being part of the “lunatic fringe” of Shroud research. But Rogers was just as critical of those who, without the benefit of solid science, declared the Shroud of Turin a fake. They, too, were part of the lunatic fringe.

The idea that the Shroud of Turin had been mended in the area from which the carbon 14 samples had been taken had been floating around for some time. But no one paid much attention. In 1998, Turin’s scientific adviser, Piero Savarino, suggested, “extraneous substances found on the samples and the presence of extraneous thread (left over from ‘invisible mending’ routinely carried on in the past on parts of the cloth in poor repair)” might have accounted for an error in the carbon 14 dating. Longtime shroud researchers Sue Benford and Joe Marino independently developed the same idea and explored it with several textile experts and Ronald Hatfield of the radiocarbon dating firm Beta Analytic. The art of invisible reweaving, Benford and Marino discovered, was commonly used in the Middle Ages to repair tapestries. Why not the shroud, they thought? They believed they saw evidence of it.

But the skeptically minded Rogers did not agree. He had already debunked every other argument so far offered to explain why the carbon 14 dating might be wrong. According to Ball, “Rogers thought that he would be able to ‘disprove [the mending] theory in five minutes’.” Instead he found clear evidence of discreet mending. He also showed, with chemistry, that the shroud was at least thirteen hundred years old. And he proved, beyond any doubt, that the sample used in 1988 was chemically unlike the rest of the shroud. The samples were invalid. The 1988 tests were thus meaningless.

In words that seem strange in a scientific journal that once had bragging rights to claim that the shroud was not authentic, Ball wrote: “And of course ‘authenticity’ is not really a scientific issue at all here: even if there were compelling evidence that the shroud was made in first-century Palestine, that would not even come close to establishing that the cloth bears the imprint of Christ.”

Ball, who was familiar with the evidence, had confirmed what all shroud researchers had been saying for years: the images were not painted. Moreover, a 2003 article in the peer-reviewed scientific journal Melanoidins by Rogers and Anna Arnoldi, a chemistry professor at the University of Milan, demonstrated that the images were in fact a chemical caramel-like darkening of an otherwise clear starch and polysaccharide coating on some of the shroud’s fibers. They suggested a natural phenomenon might be the cause. If this could be proven, the images could be explained in non-miraculous, scientific terms.

Shroud of Turin Second Face

The Shroud of Turin images may not the direct result of a miracle, at least not in a traditional sense of the word. But they are not manmade either. These seem to be the contradictory conclusions from an article in the peer-reviewed, scientific Journal of Optics (April 14, 2004) of the Institute of Physics in London. Using mathematical image enhancement technology, Giulio Fanti and Roberto Maggiolo, researchers at the University of Padua in Italy, discovered a faint image of a second face on the back of the Shroud of Turin. This has since been confirmed with other software. The implications are explosive and exciting.

This supports a hypothesis that the Shroud of Turin’s image is the result of a very natural, complex chemical reaction between amines (ammonia derivatives) emerging from a body and saccharides within a carbohydrate residue that covers the fibers of the Shroud of Turin. The color producing chemical process is called a Maillard reaction. This is fully discussed in a peer-reviewed scientific journal, Melanoidins, a journal of the Office for Official Publications of the European Communities (EU, Volume 4, 2003).

The proposal, by chemist Raymond E. Rogers and Anna Arnoldi of the University of Milan, is hypothetical. But the chemical and physical nature of the Shroud of Turin’s images is pure scientific fact.

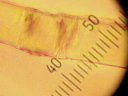

Phase-contrast photomicrograph of a fiber and its image bearing coating. The coating is composed of starch fractions and saccharides.

Imagine slicing a human hair lengthwise, from end to end, into 100 long thin slices; each slice one-tenth the width of a single red blood cell. The images on the Shroud of Turin, at their thickest, are this thin. In selective places, an otherwise clear layer of starch fractions and saccharides, a mere 200 to 600 nanometers thick, as thin as the wall of a soap bubble, has undergone a chemical change into a caramel colored substance. Spectral and chemical analysis reveal that the chromophores of the Shroud of Turin’s images are complex, conjugated carbon bonds.

Whatever the Turin Shroud is, it is not a medieval fake relic

Just as modern Christianity is a tapestry of diverse traditions stretched taut between the polarities of unwavering biblical literalism and unbridled modern revisionism, modern beliefs and arguments about the Shroud of Turin are drawn tight between those who seek from it some proof of the Resurrection and those who are rigidly skeptical. Could it be that the answer is a via media, a middle way, a reasoned embrace of the facts that implies a resurrection but does not prove or define it. For a burial shroud to survive, the tomb had to be open. There is just enough confusion to preserve the freedom to believe short of certainty: meaning faith.

If the Shroud of Turin is genuine, it presents us with more mystery and paradox than clarity. That, however, is not so perplexing as it is exciting in an age of diverse beliefs and traditions.